- The Spark

- Posts

- How one woman brought down an abusive app

How one woman brought down an abusive app

Apple was profiting from leaked and illegal images until Tansa, a small newsroom in Japan, investigated

Hey there,

A quick note before I start: this week’s story involves mention of child sexual abuse imagery and the nonconsensual sharing of intimate photos, while the second story deals with ethnically motivated violence. If that’s not something you’re comfortable reading about today, no worries – take care and I’ll see you next week.

A few massive businesses dominate the global tech industry, with market values and influence that put them on par with sovereign nations. It’s created a stark imbalance of power between us and the companies shaping our digital lives. It's easy to believe these companies are untouchable, immune to criticism and able to operate with impunity. But what happens when things go wrong? When people are harmed?

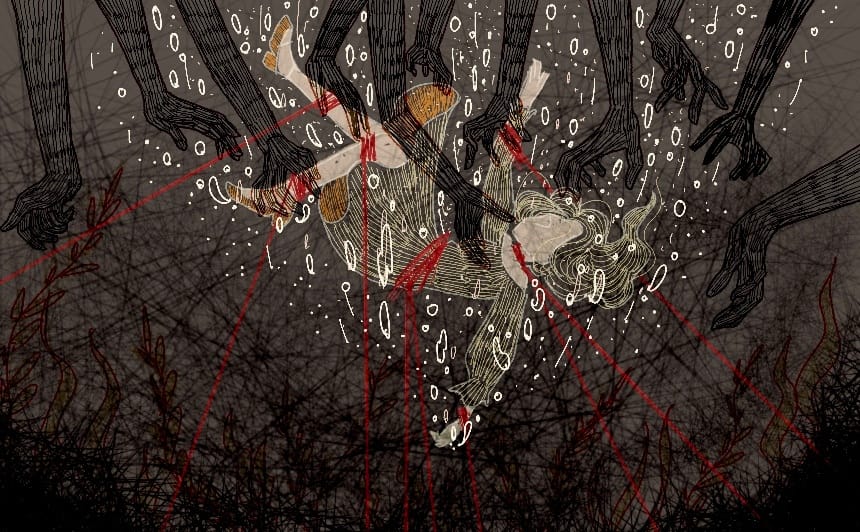

Take a photo-sharing app, for example. Images can go viral in seconds, and once released onto the internet, they’re nearly impossible to contain. That’s just as true for images that are illicit, deeply private, captured without consent or distributed without control. In the worst case scenario, a viral picture could depict violence against children. Surely, the tech giants would act to stop this?

Not always. One such app, Album Collection, became a hotbed of digital sexual abuse against women and children. It was readily available to download on the Apple and Google app stores. In December 2023, it even topped the “Photos & Videos” category in the App Store, outranking Instagram and YouTube.

But then Tansa, a small but mighty investigative newsroom in Japan, got involved. By exposing how the abuse imagery was circulating on the app, Tansa managed to get Apple to withdraw it from their app store. The team didn’t stop there: they also dug through complex corporate structures to uncover the real people behind the app. The mounting pressure eventually forced the company to shut down last year.

It was a David and Goliath moment: a small investigative newsroom taking on tech titans.

The journalist behind this feat is Mariko Tsuji. We spoke over a video call, her in Japan, me in London. Despite the distance between us, the impact of her work ripples far beyond her country’s borders.

Tsuji is softly spoken and chooses her words carefully. Her politeness is underscored by a determination and deep empathy for those whose lives have been violated online. “I started my investigation in 2022,” she told me. “One of my friends, who had just graduated from high school, found that her smartphone was hacked. Her pictures and videos were spreading and selling in the applications that people could download from Google and Apple’s App Store”. |  Mariko Tsuji |

Tsuji's friend went to the police. The police officer told her bluntly: “Speaking frankly, if [an image is] being spread like that online, it cannot be completely eliminated. There’s nothing for it but to request the photos and videos be deleted when you find them.” Her friend reported the album containing her images; it was taken down only to be reuploaded later.

Tsuji was furious at the police’s inaction and dug deeper. What she found was even more disturbing: the app wasn’t just a repository for hacked photos – it was a marketplace for child sexual abuse material.

On the app, each album or folder was protected by a password. Users had to buy the password key, for about 160 yen (roughly 80p) a pop. A person’s privacy violated, or their childhood ruined, for the price of two Freddo bars.

One of the most shocking discoveries? Apple was taking a cut. Each time someone bought access to these folders, Apple collected a transaction fee. In effect, the company was profiting from abuse.

But who was behind the app? Who was profiting from the sharing of these illegal images? Tsuji started looking into the company structure to find out who was pulling the strings. She found “Max Payment Gateway Services”, a company that for a time was registered with Companies House in the UK, including a London address. And it was overseen by a man named Keisuke Nitta.

Nitta wasn’t an easy man to find. Tsuji followed the trail from Hawaii to Singapore, London, Shibuya, and finally Nitta’s Tokyo apartment. Eventually, she had a breakthrough. Looking at corporate registers from Singapore, Tsuji came across another name, Kenichi Takahama. He was also involved in setting up Max Payment Gateway Services.

Tsuji eventually managed to convince Takahama for a sit down interview. “He defended himself by saying that he shared information with the police when illegal image transactions were found, and that he changed the app functions to prevent further harm,” she told me.

Nitta and Takahama have since requested that Tansa delete the articles pertaining to them. The articles remain online.

Album Collection no longer exists, thanks to Tsuji’s investigative work, but digital sex crimes haven’t stopped – users have simply migrated to other, similar apps.

Tsuji remains concerned: “I see no willingness on the part of major platforms, despite their responsibility to prevent digital sexual violence, or the government and police, who oversee these actors, to take digital sex crimes seriously.”

It may be a game of cat and mouse, but one that Tsuji will continue to play for the sake of those directly harmed. She credits her success to the bravery of those who had their images shared. “What sparked these changes was the courage of those directly affected and their supportive families, who shared their experiences with me.”

If you want to learn more about Tansa, the New York Times wrote a great feature piece about them earlier this year.

I taught myself to sing and I taught myself to shout

I taught myself how to get by and go without.

Jasper Jackson was, up until last month, Big Tech Editor at TBIJ. Before he went, I asked him to tell me about one of his stories: an investigation into online hate speech and what social media companies were – and weren’t – doing to stop it. |  Jasper Jackson |

“One of the first stories I published after becoming Big Tech Editor has ended up as one of the most impactful, although when we started looking into it we had little idea quite where it would go.

I had been told that fact checkers in Ethiopia, which at the time was experiencing a brutal civil war, were being given the cold shoulder by Meta, the company that owns Facebook and Instagram. Facebook said it worked with independent fact checkers to keep Ethiopians safe on the platform, but various groups told us they’d heard nothing back from the company.

With the help of local freelancers we eventually discovered a far more worrying and important story – people were being murdered in ethnically driven violence that their family members said was because of posts on Facebook.

As part of the reporting, I spoke to Abrham Meareg Amare, who said his father had been brutally murdered after being targeted with hate and lies online. At the time, Abrham couldn’t be featured in our reporting, which told the stories of two other families grieving loved ones they said were killed because of posts on Facebook.

However, I was later able to introduce Abrham to lawyers. They have used his testimony, the Bureau’s reporting and a wealth of other evidence to bring a case against Meta for its role in what is so far the most deadly war of the 21st century. They are asking for £2bn to help the victims of violence in Ethiopia, and for Meta to do more to limit the real harm it causes.

Meta has opposed the case at every step, including arguing that it can’t be sued outside the US – despite having millions of users in Ethiopia. Judges have ruled that the case can go ahead, and we are now waiting for Abrham’s day in court.”

~ Lucy here: Tech companies are becoming increasingly powerful across the world, providing services that billions of us rely on. Some of them engage in dishonest behaviour. And often they do so in the shadows, until an investigative journalist uncovers it for all to see. It can often feel like a real uphill climb, but we are determined to make sure they’re held accountable, no matter how far we have to go to reveal their actions. If you felt moved by today’s edition of The Spark, then please support us by becoming an Insider: ~

The thing I love about stories like Tsuji’s, like Jasper’s, is they remind me that despite all the power these tech businesses hold over us, the power to change the status quo is not entirely out of our hands. We can kick up a fuss, demand better and refuse to let the problem go. There may come a time to hand over the work to lawyers or regulators, but it’s amazing how often good reporting can get the ball moving.

I’d love to know what you think should be done when Big Tech companies enable – but don’t actually create – harmful content on their platforms. Should Apple and Google have taken down Album Collection themselves? Should Facebook stop hate before it reaches anyone’s feed?

(I’ve also been dying to try out this poll tool for weeks!)

Do big tech companies do enough to keep their platforms safe? |

Take care,

Lucy Nash |  |